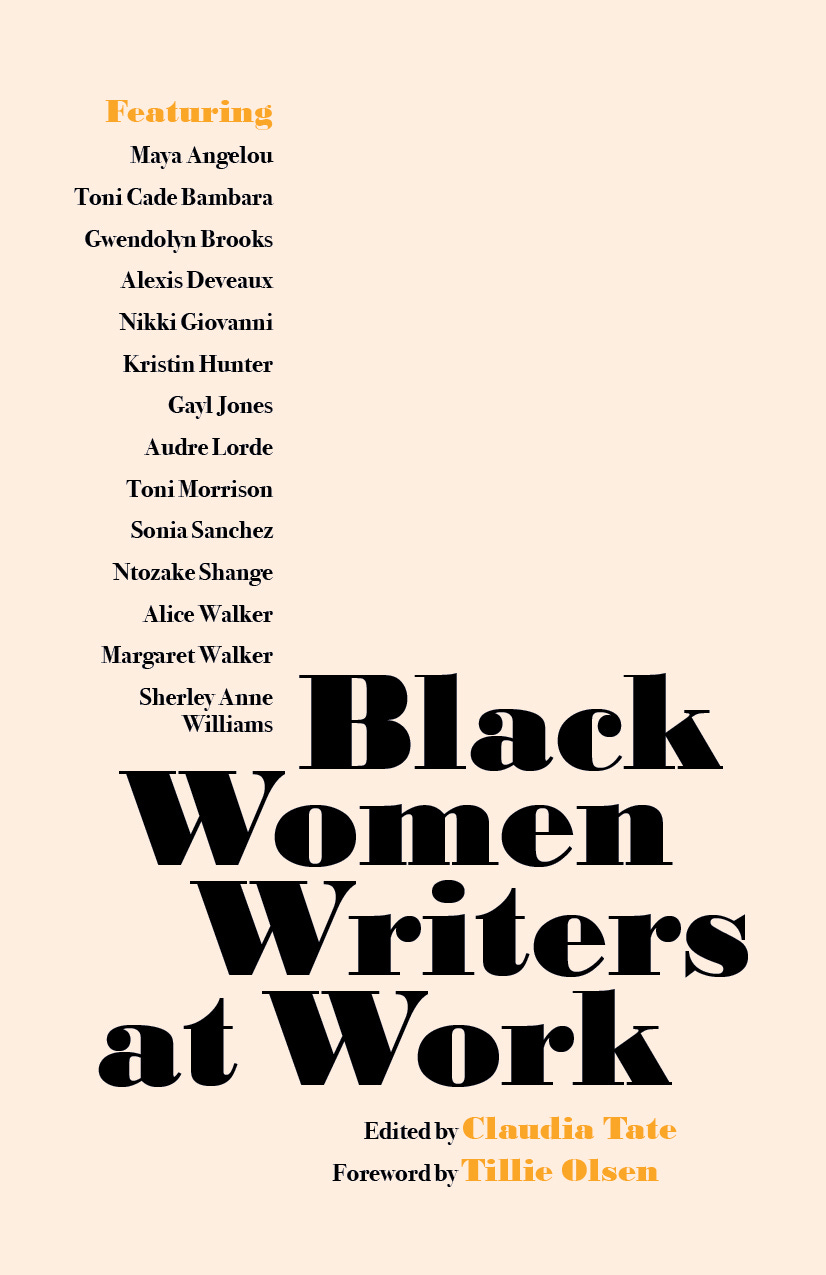

📚 Book Club This Sunday - Feb. 26th - featuring poet Diamond Sharp!

"Claudia Tate is singularly unobtrusive, asking the briefest possible questions and allowing her subjects to answer at length..."

Join us this weekend for book club. Register here! Poet Diamond Sharp will join the community discussion.

Date: Sunday, Feb. 26th

Time: 3PM EST

Below is an excerpt from an NYT book review circa 1983

Claudia Tate is singularly unobtrusive, asking the briefest possible questions and allowing her subjects to answer at length. Her main concerns are the creative process and the influence that race and gender have had on her subjects' work. We aren't told how the interviews were conducted, but largely they sound written or at any rate edited. They lack the informal, chatty style of the Mississippians' recorded conversations. This may be a drawback if you wanted a glimpse of a real live poet in her bathrobe, but it does allow the writers to present themselves where writers are most capable: on paper.

Fourteen women are included - everyone from the self-described ''black lesbian feminist warrior poet'' Audre Lorde to the poet and critic Sherley Anne Williams. There are more writers than the average reader is familiar with, but fewer than might have been included. The absence of the novelist Paule Marshall and the poet Lucille Clifton is a disappointment. For different reasons, so is that of Michele Wallace - a poet and the author of ''Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman,'' which is a diatribe against black sexism, about which nearly everyone in this collection has something very strong to say.

For sheer vitality, Nikki Giovanni takes the prize. She's as energetic as her poetry, sturdily resisting even the mildest nudges from the interviewer. Asked whether the revolution is over, she says, ''I have a problem I think I should share with you. For the most part this question is boring.'' Asked to define the black esthetic: ''It's not that I can't define the term, but I am not interested in defining it.'' On black sexism: ''I have problems with this man-woman thing because I'm stuck on a word. The word's 'boring.' '' But what she does want to answer she answers beautifully, as in her discussion of black music's evolving from the sound of women calling to women across the fields.

Toni Morrison shines out for her articulateness; there's something complete and satisfying in her discussion of her novels. Another novelist, Gayl Jones, gives thoughtful, grave responses, while Alice Walker comes across as spunky and forthright. And Gwendolyn Brooks, at 65, defends herself with dignity against any implication that her early poems might not have been as assertive as black poetry today: ''I'm fighting for myself a little bit here because I believe it takes a little patience to sit down and find out that in 1945 I was saying what many of the young folks said in the sixties.''

On creative method, there's the usual wide variety of approaches, ranging from Maya Angelou's no-nonsense, roll-up-your-sleeves craftsmanship in autobiography to Toni Cade Bambara's mad dashes through her fiction: ''I babble along, heading I think in one direction, only to discover myself tugged in another, or sometimes I'm absolutely snatched into an alley.'' Alexis Deveaux, whose most recent book is a biography of Billie Holiday, addresses the writer's ''responsibility of sight,'' while Ntozake Shange, the author of the magnificent ''Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo,'' says that her own responsibility is honesty and the best possible use of her technical skills.

Oddly enough, an issue raised in many of the interviews is not black as opposed to white writing but women's as opposed to men's writing. With few exceptions, these women feel that women are more concrete, more oriented toward the particular, more comfortable with emotions. Only Toni Morrison brings up the subject of black women's writing as opposed to white women's writing. Black women, she says, seem more willing to handle aggression and adventure.

There’s a strong sense of anger in this book. Many of the women have led difficult and discouraging lives. Just look at the employment record of Margaret Walker, the author of the novel ''Jubilee,'' who also appears in the Mississippi collection. Or observe Sonia Sanchez, the poet, as a stuttering child, helpless to object when white people patted her head. (She isn't the only one to have suffered an early block in expressing herself. Kristin Hunter, the novelist, was effectively muted by a household in which children were seen but not heard. Audre Lorde did not speak at all till she was 5.) Even now in the 1980's, several women voice the feeling that because they're black, they have no hope of being read.

What gives the book a special edge, of course, is that all at once black women writers are being read. ''The Color Purple'' by Alice Walker recently won both The American Book Award for hard-cover fiction and the Pulitzer Prize. ''The Women of Brewster Place'' by Gloria Naylor won The American Book Award for a first novel. So you might say this collection is like a glimpse of someone in a doorway, one foot raised to step forth. While ''Mississippi Writers Talking'' fixes its subjects in time and place, ''Black Women Writers at Work'' follows people in motion. They are no longer where we last saw them. They have already moved into the light.